G-AMSV Returns to Coventry

An old friend returned to Coventry yesterday when G-AMSV, in her striking Indian Air force livery, landed here for extensive maintenance by our engineers. Sierra Victor was part of the Air Altantique fleet here for many years. She'll...

Baginton Air Pageant

The initial details for the Baginton Air Pageant are up on the website! As we don't have the space for a full-on air show attracting 20,000 or so people, we're aiming for low-key, themed days like this. A couple of thousand people,...

Newquay Pleasure flights

We promised we'd be back to fly in Cornwall, and here we are. We'll be heading south with a Rapide and Chipmunk to spend a week at Newquay from 25th July, with a further visit planned in August. The flights are bookable in the normal...

New Dakota Book

Geoff Jones just told me that his new book on the DC-3, released to celebrate the 80th anniversary of the Dak's appearance, is now available. The cover sports a lovely shot of G-ANAF, shot by Simon Westwood before her radome goiter was...

Nimrod Engine Run

We've just confirmed plans by NPT to run all four of the Nimrod's Rolls-Royce Speys on Saturday 9th May. We expect the thunder to start just after lunchtime. Come along and enjoy some audio power - and please dip into your pockets...

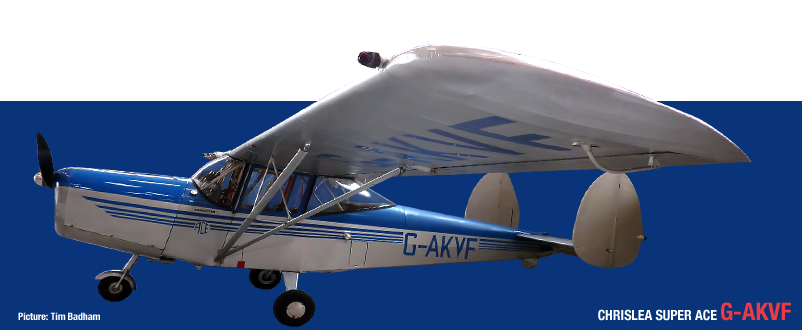

Following an interruption of operations caused by World War II, Chrislea Aircraft Ltd, launched a revolutionary new light aircraft design in 1947.

By this time, all aircraft used an essentially similar control system, still used today. Using either a joystick or yoke (similar to a steering wheel), the pilot controlled the elevators by pulling back or pushing forward. The ailerons were moved by moving the stick or turning the yoke left and right. The aircraft's left/right attitude was controlled by two pedals that moved the rudder.

Chrislea decided there was a better way, and threw away the rudder pedals. They settled on a system using dual-control yokes. Aileron control was similar to other yoke-operated aircraft: turn left for left bank, and right to bank right. So far so good...

Now for the elevator. Push or pull on the yoke on a Chrislea and nothing happens - though there's a rumour that some pilots actually pulled hard enough to break them off! These pilots were, predictably, unavailable for comment. In a Super Ace, you move the yoke up to pitch the nose down, and down to pitch the nose up. In fairness, this isn't as backwards as it sounds, but it does mean that you can't relax your arms without inadvertently climbing.

Moving the rudder involves pivoting the whole yoke left or right on its universal joint. Again, it's actually not that strange once you're used to it, but it's a different experience from any other aircraft. Many were converted to conventional control systems, and Classic Airforce's Super Ace is one of these examples.

The first production example of the Super Ace flew in February 1948, powered by a deHavilland Gipsy Major 10 piston engine. It had a single fin and rudder, but this was soon re-designed to the twin-fin set-up.

Construction of a production run of 32 aircraft was commissioned, however only 18 Super Aces were completed and flown, possibly because of the control system's unpopularity. Of these 18 aircraft, only three remained in the UK. Two of these remain in flyable condition, one of which is living happily in Newquay. It's an airborne oddity that we have to preserve, at least to remind us that, as late as the 1940s, aviation was still a highly experimental discipline.